Held in the warm month of October, the Japanese Tea Ceremony at Agora Village brought together a select group of guests from The Diplomatic Club, local artists, and cultural enthusiasts. The evening was designed to share a taste of cha do, the Japanese “Way of Tea,” and the graceful philosophy that has shaped it for centuries.

Though this was a demonstration rather than a formal ceremony, it carried the same spirit of refinement. Guests dressed as they pleased, yet all were mindful of the modesty and respect central to Japanese culture. The setting felt quietly elegant: a soft buzz of conversation, the scent of matcha, and displays of Japanese artistry—fans, a pagoda umbrella, and silken kimonos suspended like floating works of art.

Conversation during the ceremony follows a code of mindfulness. It is meant to reflect the beauty of the moment: thoughtful, appreciative, and never idle. As the host explained, talk should harmonize with the atmosphere. It was this principle that lingered with me—the art of being fully present, of noticing the quiet poetry within simple acts.

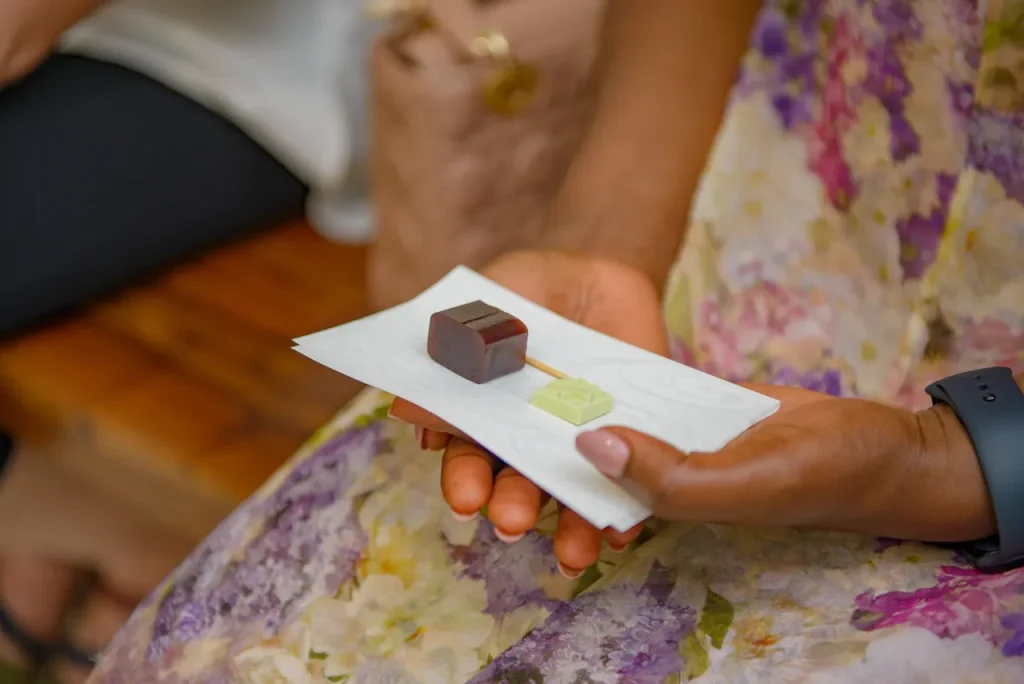

Before tea is served, guests receive two types of sweets. The first, omogashi, is soft and often made from sweet bean paste or seasonal ingredients. The second, higashi, is a dry confection that melts gently on the tongue. Each sweet prepares the palate for the unsweetened tea to come. Guests wait for the tea master’s signal before tasting them, an act of shared patience and respect.

The tea itself is made from the finest matcha, whisked to a vivid green froth. Its taste is bright, earthy, and slightly bitter, awakening both the senses and the spirit. Guests lift the bowl with both hands, bow lightly in gratitude, turn it slightly before sipping, and take measured tastes. A soft slurp at the end is not impolite but a mark of appreciation, a sign that the tea has been fully enjoyed.

Every detail held meaning, even the choice of utensils. Because the ceremony took place in summer, the bowls were lighter and designed with open, airy motifs—distinct from the heavier ones used in winter. This sensitivity to season is part of the Japanese aesthetic: an awareness of transience, of moments that cannot be repeated.

As the ceremony drew to a close, serenity lingered in the air. The demonstration had offered more than tea; it offered an invitation to stillness. In the quiet choreography of cha do, one finds a gentle reminder of how to live—with grace, attentiveness, and gratitude for the simplest of moments.

Did You Know? The Philosophy Behind the Way of Tea

The Japanese Tea Ceremony, or cha do (literally “the way of tea”), is far more than a ritual of preparing and drinking matcha. It is a quiet philosophy — an art form rooted in simplicity, discipline, and appreciation for the present moment. Every movement, object, and pause expresses four guiding principles:

Harmony (wa)

A sense of balance and connection — between host and guest, between people and nature, and between mind and surroundings.

Respect (kei)

Every object and person involved in the ceremony is treated with dignity. Even the tea bowl is bowed to, a gesture of gratitude and awareness.

Purity (sei)

Purity is both physical and spiritual. Utensils are cleansed before use, and the act of preparation clears the mind as much as the tools.

Tranquility (jaku)

The ultimate goal of the ceremony. Through mindful repetition and quiet appreciation, one reaches a state of calm that extends beyond the tea room.

The spirit of cha do reminds us that refinement lies not in extravagance, but in awareness — in finding meaning in the simplest of gestures, and beauty in silence itself.